Kicking off the project!

The Climate Change and Heritage Adaptation project began with an online conference. The two-day online conference invited projects working with or impacted by climate change in the broader North and East Africa region to share their experiences. Discussion sessions opened dialogue across geopolitical and social boundaries to help share the lessons learned by working in these areas. The diversity in projects, speakers, and communities represented at the conference reflected a similar variety of challenges faced by tangible and intangible heritage across the region. HRH Princess Dana Firas (Jordan) called for global partnership moving forward in facing those challenges while John Darlington (World Monuments Fund) noted the skills of heritage specialists in interpreting long-term visions of change. The conference ended on a message of hope - that heritage demonstrates the adaptability and resilience of people and the environment in facing up to the changing climate. A full report will follow, but you can still read the schedule and abstracts below.

Organising Committee

Prof Mohamed Abdrabo (ARCA, Alexandria University)

Dr Corisande Fenwick (British Institute for Libyan & Northern African Studies and UCL)

Dr Kennedy Gitu (British Institute in East Africa)

Dr Carl Graves (The Egypt Exploration Society)

Dr Penelope Wilson (EES Delta Survey and Durham University)

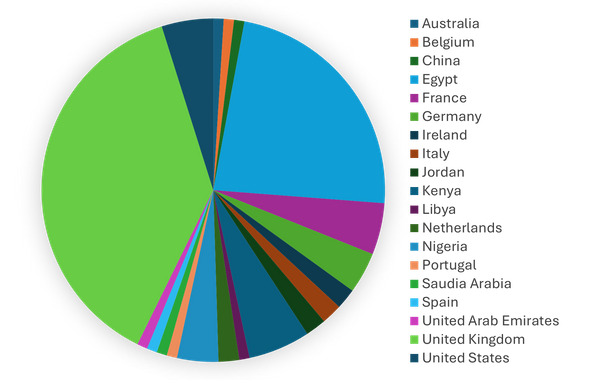

The conference was attended by 103 people from 19 different countries (see below). Nouran Ibrahim and her team of translators provided live translation from English-Arabic and Arabic-English throughout the online conference.

Attendees to the online conference by country

14 papers were presented covering broad themes related to historic and anthropogenic (human action) climate change and its impact on cultural heritage. Site-based case studies included Petra (Jordan), Amarna (Egypt), Cairo (Egypt), Lamu (Kenya), Lalibela (Ethiopia), the Jos Plateau (Nigeria), and Ngorongoro Lengai (Tanzania). Alongside these examples, larger-scale (macro) heritage landscapes were presented as well as projects working on community-led (micro) adaptation and climate-heritage justice.

Partners of the EES, BIEA, and CBRL presented papers, specifically: The Amarna Project, Egyptian Heritage Rescue Foundation, Petra National Trust, and Safeguarding Sudan's Living Heritage.

The conference was opened by Dr John Darlington (World Monuments Fund) who stressed the message of hope that heritage has to offer in discussions of climate change. As he noted, heritage specialists have the unique skills to look back at changes over long periods of time, which can also be used to model future scenarios. The adaptability of humankind during previous change helps us to find solutions, though with the need to scale these up because of rapid population rise over recent centuries. John also made the argument that historic technologies and structures could be resurrected to supplement supplies (i.e. fresh water - sabils, and cooling winds – mulqaf/mahrabiya) which has already been explored at Nabataean sites in Jordan, the Sinai Peninsula, and is under current review at locations in historic Cairo. John concluded with the message of inspiration from the past, informing our future.

Climate change is the biggest threat to the coastline, countryside and historic buildings we care for.

The keynote lecture given by Leena Mekawi (Egyptian Heritage Rescue Foundation, EHRF) and Heather Jermy (National Trust, Blickling Estate) explored the International National Trusts Organisation (INTO) Withstanding Change Project work at their two sites. Heather noted that, while it may not seem immediately apparent, both sites are facing similar challenges regarding water management. International partnership between EHRF and National Trust had revealed several solutions to curb the flow of water, remove excess water naturally, and to aid water run-off. This included the rechannelling of natural water courses based on natural historic (i.e. pre-canalisation) routes, and the planting of trees. Humidity remains an ongoing threat as well as water falling on flat roofs on both sites. This is a growing threat as rainfall becomes more frequent, heavier, and/or prolonged based on climate change modelling.

The National Trust and Climate Change

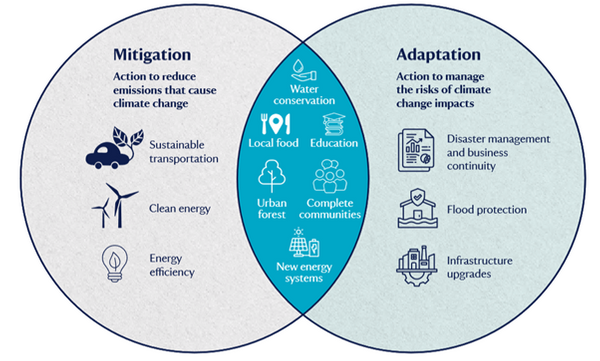

The National Trust have developed a flexible ‘Adaptation Handrail’ for their heritage properties which includes developing an impact assessment and holding workshops with local teams before taking action:

The INTO project has also worked with the National Trust to deliver climate change adaptation guidance for heritage practitioners:

https://www.into.org/new-national-trust-climate-change-adaptation-guidance/.

The National Trust outline for understanding mitigation and adaptation and where actions intersect.

Adaptation requires global collaboration, shared challenges, and inspired solutions.

Other key messages that came from the conference included:

- We must understand the current heritage situation in order to know what is at risk and to prioritise recording and monitoring, particularly where the risk is so great that preservation can only be achieved by record (i.e. where managed retreat is recommended). For example, 94 m of Kenyan coastline have been lost since 1994 at an average rate of c. 4 m per year. This threatens more than 45 historic sites, as well as communities based there. Mapping is already completed, but the recording of tangible and intangible heritage is ongoing.

- Climate change disproportionately affects local communities which can lead to imbalances in social structures, especially if non-local heritage practitioners are used. A vulnerability assessment could be used to help this process feel more equitable. This should include stakeholder mapping as well as understanding the needs and priorities of local communities. For example, the local communities around Petra, when asked, defined their priority for income as agriculture and not tourism as the latter is seasonable and unreliable. Basically, there is no ‘one model fits all’ approach as communities have diverse identities, origins, and needs.

- Climate change can lead to population movement. Not only does this threaten tangible heritage in their new location (i.e. archaeological sites often provide protected land for habitation above sea level), but also a loss of intangible heritage which was tied to their tangible surroundings. Both tangible and intangible heritage are important to protect, and are rarely easy to separate.

Lamu Old Town (Kenya) sea front is at risk from sea level rise. Image by Njiiri Wallace.

- Community-centred approaches through consultation and active participation can result in a higher degree of adoption of adaptive methods (i.e. Megawra’s work in historic Cairo to re-green spaces using groundwater damaging heritage monuments). Engaging children in Sustainable Development Goals and climate change mitigation embeds learning in the community allowing heritage organisations to become a cross-community safe space for peace building. For example, the Safeguarding Sudan’s Living Heritage project has utilised shelters and cultural spaces for bringing communities together in the face of climate change and conflict showing that climate change does not affect heritage in isolation. Furthermore, museums (such as the National Museum of Alexandria) and other cultural centres are already established spaces within communities and can be used to expand educational reach and engagement.

- Working within local communities can also reveal adaptive solutions already in use and familiar to them. While they may not have the tools to scale these up, heritage practitioners can work with them to promote a bottom-up approach, thus empowering these communities further. For example, villagers living in the heritage landscape of the Jos Plateau in Nigeria were already aware of the impact of climate change on their agricultural way of life but had implemented small adaptive measures to secure farmland and the stability of it. This included abandoning traditional methods of slash-and-burn farming and planting of crop-yielding trees to stabilise land facing increasing aridity. By bringing neighbouring village leaders together, this practice could be shared, thus benefiting a wider region. This example also demonstrates the need to consider multiple scales of adaptation and delivery – from the micro (household) to the macro (landscape).

Traditional farming techniques adapting to climate change on the Jos Plateau of Central Nigeria. Image by Na’ankwat Kwapnoe-Dakup.

- The modern rate of climate change is a major factor in loss and damage. While change has existed in the past, it was not at the rate seen today which is a direct result of anthropogenic climate change. Flora and fauna have previously adapted based on climate change and it may now be possible to consider the reintroduction of species into environments where they previously existed (i.e. gazelles in north Africa). Genetically modified crops are also less adaptable to changes in climate and so re-introducing heritage species (based on research) may be a solution to poor yields. However, this may have an impact on the carrying capacity of the land and thus cause further issues. These solutions are also hindered by modern geopolitical borders which intervene to stop ease of population movement.

- Some responses are pro-active (rather than reactive) to future threats. This can appear, initially, as wasted resources on non-priority activities but are critical to safeguard heritage. Regrettably, funding is not often available for heritage sites working pro-actively. The Amarna Project worked on understanding the wider environment of the archaeological site when developing their site management plan which included discussion of potential climate hazards, though this could be expanded.

- Some archaeological materials are not yet fully understood with regard to their intrinsic resilience, including rock-hewn architecture (i.e. Lalibela, Abu Simbel, etc.) and mudbrick (i.e. Amarna). Further testing must be carried out but could include soft-capping of rock structures to protect them from rainfall, reconstruction with modern materials (which?) of mudbrick structures, reducing salinisation by planting trees which in turn provide shade and absorb carbon. The latter is an example of cross-over between mitigation and adaptation.

A modern drainage system in the royal wadi at Amarna in Egypt. This is designed to channel flash floods away from monuments as a pre-emptive measure. Image by the Amarna Project.

- Currently, there is a lack of engagement between heritage practitioners and policy/law-makers. This results in a lack of enforcement, implementations, and involvement in the solutions necessary to safeguard tangible and intangible heritage.

- The MENA region will be disproportionately affected by climate change with an estimated increase of c. 4°C by 2050 compared to 1.5°C globally. Those working in the region must take a scientific and values-based approach to measuring risk and resilience in order to suggest relative, workable, and realistic measures for mitigation and adaptation.

Partnership is crucial if we are to move the discussion around climate-adaptation forward.