The Umbarak family

by Susan Biddle

One of the delights of exploring the EES Lucy Gura Archive is to uncover the stories and identities of the Egyptian workers that helped on the Society’s digs over the past century. All too often these individuals are overlooked or remain anonymous except in records of pay and perhaps an elusive name on a record card. Without them however, none of the work of exploration and discovery would have been possible. In this brief highlight, Susan Biddle unlocks the history of a single family, the Umbaraks that helped at Amarna in the 1930s.

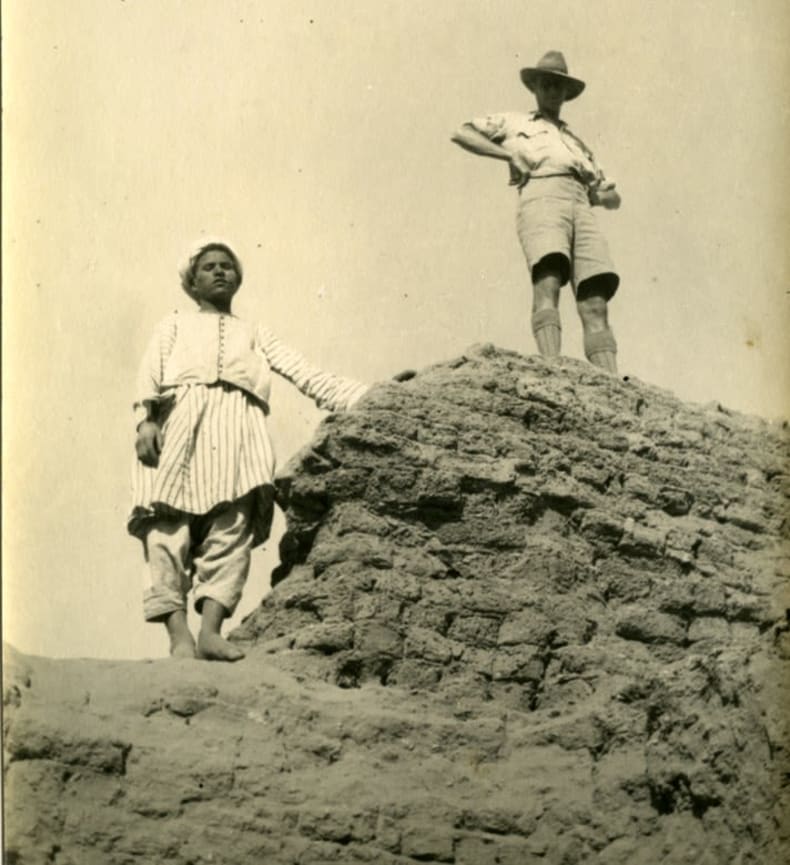

The Umbaraks were a family of Guftis working with John Pendlebury at Tell el-Amarna in the early 1930s. In her book, Nefertiti Lived Here, expedition team member (and EES assistant secretary at the time) Mary Chubb described the Umbarak family when they first arrived at the start of the season: old Umbarak, the head reis, wrinkled and a little anxious, and his three sons: Mohammed, burly and placid, Mahmud, much more delicately built and nervous, and then Kassar, “a beautiful stripling with wonderful long-lashed eyes and a lock of jet-black hair escaping from his saucy turban”. These evocative and personal descriptions inspired me to search for these people and I was delighted to find, in the archive, a photograph of Kassar which he had enclosed with a letter to Hilary Waddington. Indeed he fits Chubb’s wonderful description well, though you are able to form your own opinion of him from the image itself:

Kassar Umbarak el Beladi (L) with Hofni Mahudi during the 1930-31 season, TA.WAD.01.PICT.08.

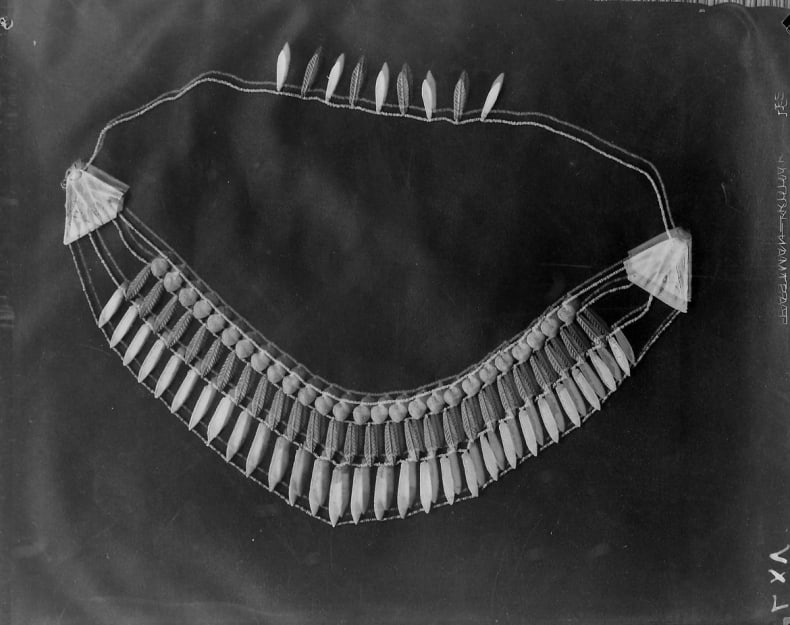

Kassar was not just ‘beautiful’. Chubb tells us that, when a complex necklace of pendants and beads was found, it was Kassar who ran the mile up to the dig-house to ask Mary and Hilda Pendlebury to help lift it. And at the end of the day, when Mary had drawn the necklace and laid it out in order on the drawing board, it was Kassar and another young Gufti who carried the board up to the house without disturbing a single bead. This was similar to the necklace of three rows of beads with faience end-pieces found in house S.35.4 and illustrated in City of Akhenaten II, and now in the British Museum (EA 59334).

Image TA.NEG.28-29.0111 showing the beaded collar, though the image is less clear than that published.

The other members of the Umbarak family also feature in Mary’s account of life on the dig. At the close of season fantasia, it was Kassar’s elder brother Mahmud who “began very seriously an intricate dance. It was mostly neat footwork … but at the same time he made slow beautiful movements with his arms, now sweeping his white staff about his turbaned head, now holding it along his shoulders in small delicate fingers … the austerity of the Guftis seemed epitomized here, as Mahmud, the lashes of his downcast eyelids almost resting on his high cheekbones, gravely and beautifully circled the courtyard, intent only on the technical perfection of his dance.”

Like his brother, Mahmud was also a skilled worker. In his preliminary Report of excavations at Tell El-Amarnah 1930-1 (JEA 17, 1931: 241) John Pendlebury reported that the fact they could plan house U.25.8 “must be put entirely to the credit of the workmen and particularly of a young reis, Mahmud Umbarak. Of the house itself not one brick remained. At first it looked as though we were tracing flowerbeds, but thanks to careful scraping on the part of the “company”, not by any means entirely composed of trained men, the slight darkening of the sand where bricks had once been revealed the walls and even the thresholds of doors. The plan itself showed nothing new, but our delight in the care and skill of the men repaid all the trouble.”

In an earlier season at Amarna, Mahmud had found a small solid gold ring, and he and his father also acted as guards at the site out of season during 1931.

Kassar was on friendly terms with Hilary Waddington, who worked with Pendlebury as architect and camera-man (see more about Hilary Waddington and his work at Amarna here). When Hilary married in 1932, Kassar sent him and his wife, Ruth, a wedding present of “two fans for giving air” and a plate, and “begged our Lord God to give you nice and strong children” (TA.WAD.01.034). In a letter from Hilary to John Pendlebury, we learn that the plate was “hung with cowry shells (to bring luck in connection with certain events!)” (TA.WAD.01.038).

Kassar and his family were keen to work on the dig again. At that time Hilary was working at Athlit with C N Johns and in his thank you letter to Kassar, Hilary mentioned that he might need some Guftis there (TA.WAD.01.048). In an earlier letter to John Pendlebury, Hilary had been concerned about employing Kassar at Athlit because he “is rather good looking and I don’t want to spend too much of my time pacifying irate fathers of deflowered daughters! Besides it looks bad” (TA.WAD.01.046). Hilary hoped that the presence of Kassar’s uncle Adito at the museum might be a sobering influence but in fact he did not need to worry – in his reply (TA.WAD.01.049), John Pendlebury reassured Hilary that Kassar was now married; the same letter reported that Kassar was paid PT 7, half his father’s pay of PT 14, but more than the PT 5 paid to Abu Bakr the young houseboy.

Another glimpse of the Umbarak family was revealed in the Amarna correspondence archives, where I found a postscript on a 1929 letter from Hans Frankfort, director of the Amarna dig before Pendlebury, reporting to Stephen Glanville that “Umbarak has borrowed (or taken) the money which his various sons got at Armant and went and bought another wife for 15 guineas.” I have not yet discovered whether the Umbarak brothers thought their pay well spent on a new step-mother.

Kassar Umbarak with Seton Lloyd, another member of Pendlebury’s team, at wadi house T.34.2 during the 1930-31 season, TA.WAD.O1.PICT.13.

As well as preserving the history of great institutions, archives are about people and their personal narratives. Though we only know snippets of the life of the Umbarak family, using both the library and archive together has opened a window into their world and the ways in which they too contributed to the understanding of Egyptian heritage. In doing this, their own heritage is also richer and count among thousands of, as yet, untold stories.