Unearthing Tutankhamun

Who was Tutankhamun?

Head of Tutankhamun, Amarna Period, c. 1336–1327 BCE, (MMA 50.6). The hand of the god touching the back of the young Tutankhamun's head represents his investiture as king.

Tutankhamun ruled Egypt from about 1332-1322 BCE, during the period known as the New Kingdom.

He was probably the son of the so-called ‘heretic pharaoh’ Akhenaten, who worshipped the sun disk above all other gods and founded a whole new city dedicated to it.

After Tutankhamun came to the throne at about nine years old, work began to put things back as they were. Later kings tried to remove all traces of anything connected to Akhenaten, which included Tutankhamun. His name was almost lost to history.

So how did Tutankhamun go from barely-remembered to one of the most famous pharaohs of all?

Howard Carter comes to Egypt

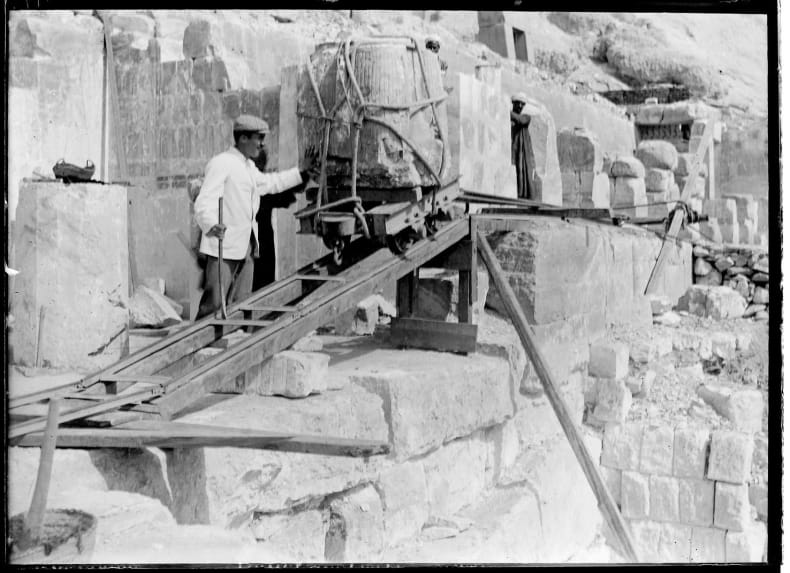

In 1891, a 17-year-old called Howard Carter began his first season of fieldwork in Egypt. He had no previous archaeological background, but after working as a painter on the Egypt Exploration Fund (now Society) projects at Beni Hasan and Deir el-Bersha, a passion for excavation took root.

Image: Howard Carter working at Deir el-Bahari for the Egypt Exploration Fund during his early 20s (EES.DB-HAT.NEG.04.40)

In 1899, Carter was appointed to the Egyptian Antiquities Service, which at that time was run by British and French scholars. He resigned from the Service in 1905 after a fight with a group of tourists, instead making his living as an artist and antiquities dealer in Luxor.

The Quest for the Boy King

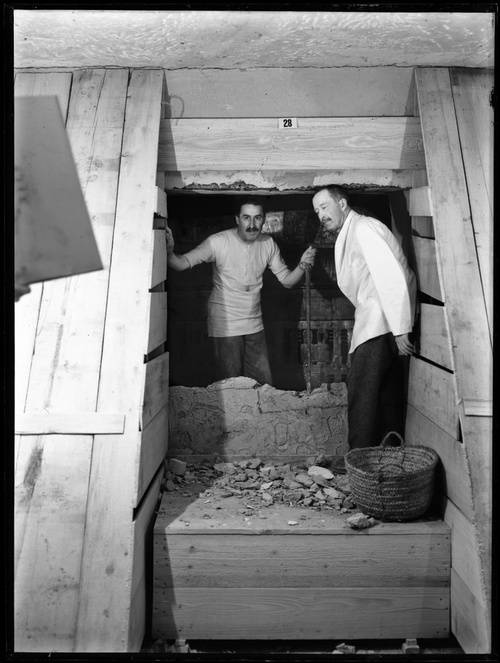

Image: Howard Carter (left) and Lord Carnarvon (right) in the tomb of Tutankhamun, (Burton p0291 © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford).

In 1907, Carter met his future patron Lord Carnarvon. He went on a series of Egyptian tours from 1901 onwards, but before long, he was running excavations with Carter. They dreamed of excavating in the Valley of the Kings, the burial ground of the New Kingdom pharaohs, and after years of work, they finally got the chance. Carter wanted to find an unopened royal tomb, and believed his best chance lay with an obscure king whose burial had not yet been identified: Tutankhamun.

The search began in 1917, but for five years the excavators found hardly anything. Lord Carnarvon was worried; he couldn’t keep pouring money into excavations for no results. But Carter convinced him to fund one final season, focusing on the last area Carter thought might have something to reveal.

The gamble paid off on 4th November 1922 when the Egyptian excavators discovered the top of a staircase. Clearing out the debris revealed a sealed doorway, the plaster stamped with the seals of Tutankhamun and the royal necropolis. However, they could see the door had been opened and re-sealed in antiquity, probably after attempts to rob the tomb; would the team find nothing but empty chambers?

The 26th November was, in Carter’s words, ‘the day of days’. The excavators had reached another sealed door at the end of the passageway. Carter made a small hole in the plaster, and holding a candle to it, he saw ‘strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold’.

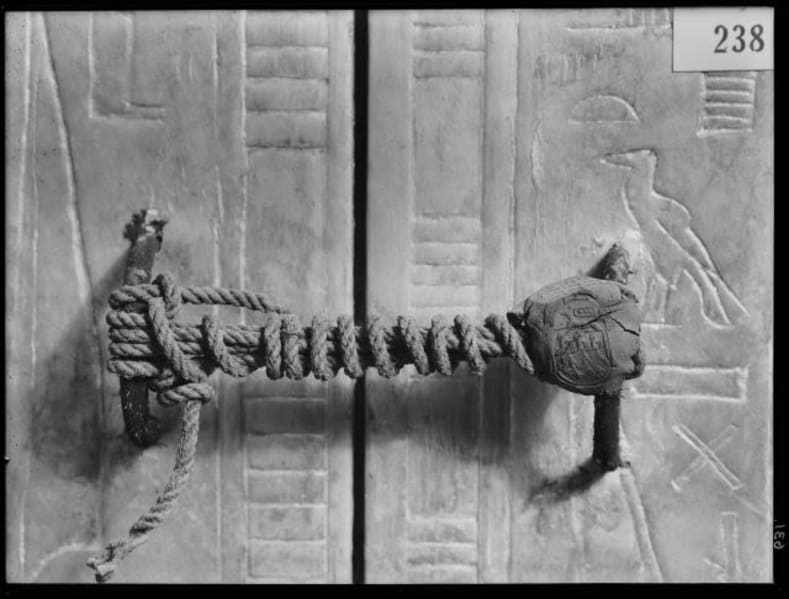

The intact seal on the third golden shrine surrounding Tutankhamun's sarcophagus in the burial chamber, (Burton p0631 © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford).

The Tomb and its Contents

Tutankhamun’s tomb (numbered KV 62) is small, containing just four chambers, and only the burial chamber is decorated. This is probably because the king died unexpectedly, so a tomb had to be prepared quickly.

Image: Burial goods within the southern end of Tutankhamun's Antechamber, (Burton p0012 © Griffith Institute, University of Oxford).

The antechamber, annexe, and treasury were piled high with luxury objects, while the burial chamber was almost entirely filled by a set of four golden shrines nested one inside the other. At the centre lay the king’s sarcophagus.

The tomb had indeed been opened before – twice! – but many of the king’s treasures had survived the robberies, most famous of all being the iconic golden death mask that covered the head of the Tutankhamun’s mummy. The long-forgotten boy king captured the world’s imagination, and 100 years later the discovery of his tomb is still one of the greatest archaeological finds in history.

Tutankhamun's golden mask.

Have a go at designing your own golden mask!

Download a template here

Complete our Unearthing Tutankhamun word search!

Download the activity here

Learn more

- Find out more about Tutankhamun's life, death and afterlife here.

- Browse Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation at the Griffith Institute - the definitive archaeological record of Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon's discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun.

- Visit the current exhibition Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive by the Griffith Institute at the Bodleian Libraries in Oxford (13 April 2022 – 5 February 2023).

- Read the book Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive, "an essential text for all readers who wish to get a better sense of this world-famous discovery", as "the accessible layout and stand-alone content make it an equally important publication for those who cannot visit the exhibition" (Anna Garnett from a book review in Egyptian Archaeology 61).