Charles Dudley Warner’s Winter on the Nile

by Hazel Gray

As well as Henry Villiers Stuart's Nile Gleanings, the Walker Bequest of books includes another travel account written by an early member of the Egypt Exploration Society. This time it is an American author and editor, Charles Dudley Warner, who began by donating $5 a year to the Egypt Exploration Fund, and rose to be one of its US Vice Presidents during the 1890s.

Charles Dudley Warner c. 1897 (US Library of Congress)

Charles Dudley Warner was born on a farm in Massachusetts in 1829, then moved to New York state following the death of his father. After college, he worked as a railroad surveyor, hoping to improve his health and raise some much-needed cash. He graduated from Pennsylvania Law School in 1858 and spent two unhappy years practising law in Chicago. An old friend, Joseph Roswell Hawley, invited Warner to join him in Hartford, Connecticut, as co-editor of a local paper, and he jumped at the chance, setting up home there with his wife Susan in Nook Farm, a colony of well-connected writers, artists, politicians and activists that included Harriet Beecher Stowe and Mark Twain.

In 1870, Warner’s journal The Courant published a series of his light-hearted essays about working in his garden, later re-published in book form as My Summer in a Garden, which became a best-seller. Other essays and travel books followed, as well as a collaboration with Mark Twain called The Gilded Age, and by 1880, Warner was one of America’s most popular writers.

A first edition copy of The Gilded Age by Warner and Twain

Between 1870 and his death, among other travels, Warner made five journeys to Europe and the Middle East, leading to nine travel books. My Winter on the Nile: among the mummies and Moslems was published in 1876 and is described as ‘perhaps the acme of Warner’s achievements in his books of travel’ (Fields 1904:54-5).

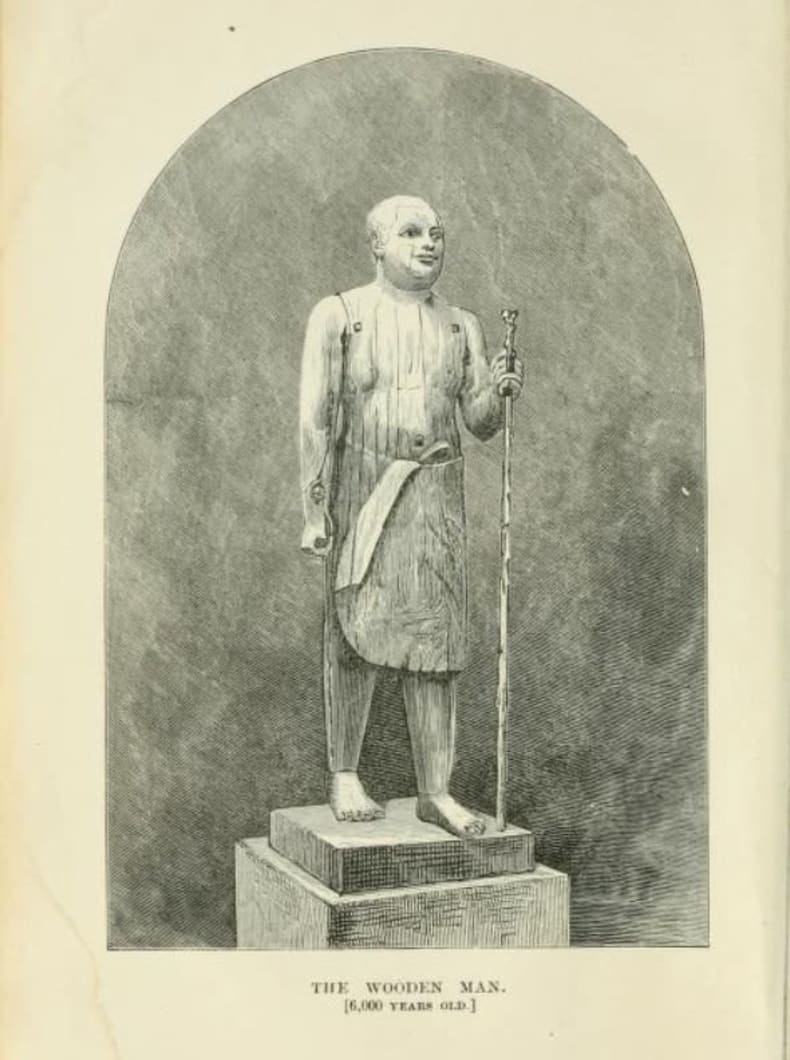

'The wooden man' as the frontispiece of Warner's Winter on the Nile

Warner gives us a humorous and detailed view of his journey up the Nile, and the day-to-day life and excitements of the voyage, with his dragoman (interpreter, translator, and guide) Abd-el-Atti emerging as one of the great characters of the book.

He first describes some of the essential preparations before any Nile voyage could begin.

‘Two other necessary articles remain to be procured; rockets and other fire-works to illuminate benighted Egypt, and medicines… In the opinion of our dragoman it is scarcely reputable to go up the Nile without a store of rockets and other pyrotechnics… The common fire-works in the Mooskee he despised; nothing would do but the government-made, which are very good.’

Christmas was celebrated in Asyut.

‘In the evening, with the dahabeëh beautifully decorated and hung with colored lanterns, upon the deck, which, shut in with canvas and spread with Turkish rugs, was a fine reception-room, we awaited our guests… as if we usually celebrated Christmas outdoors, fans in hand, with fire-works… The Pasha was received as he stepped on board with three rockets… Coffee and pipes are served on deck, and the fire-works begin to tear and astonish the night. The Khedive certainly employs very good pyrotechnists, and the display by Abd-el-Atti and his equally excited helpers, although simple is brilliant.’

Later in Esna, Abd-el-Atti’s love of fireworks would lead to an angry visit from the governor, after a rocket from an arriving boat started a fire in the town. It could not be proved who had fired the rocket, but it was a government firework, of the type preferred by Abd-el-Atti, and, though no further action was taken by the governor, he feared for his reputation: ‘How it’s all right? Story go back to Cairo; Rip van Winkle been gone set fire to Esneh. Whose rockets? Government rockets. Nobody have government rockets ‘cept Abd-el-Atti.’

The cover of My Winter on the Nile (18th edn) depicting a dahabiyah

Warner remarks on the lack of accommodation for tourists outside Cairo, and his thoughts on potential developments are prescient.

‘There is not indeed in the whole land of Egypt above Cairo such a thing as an inn… With steamboats making regular trips and a railroad crawling up the river, there is certain to be the Rameses Hotel at Thebes before long, and its rival a Thothmes House; together with the Mummy Restaurant and the Scarabæus Saloon.’

Such accommodation would surely be necessary for future travellers, for he remarks on the immensity of the ruins in ancient Thebes.

‘You need two or three weeks to see properly the ruins of Thebes, though Cook’s “personally conducted tourists” do it in four days. The region to be travelled over is not only vast…but it is exceedingly difficult getting about, and fatiguing, if haste is necessary… Perhaps the easiest way of passing the time in an ancient ruin was that of two Americans, who used to spread their rugs in a shady court, and sit there, drinking brandy and champagne all day, letting the ancient civilization gradually reconstruct itself in their brains.’

And he tells us of the flourishing trade in antiquities:

‘This [mummy’s] hand has been “doctored” to sell; the present owner has re-wrapped bitumen-soaked flesh in mummy-cloth, and partially concealed three rings on the fingers. Of course the hand is old and the cheap rings are new… Great quantities of antique beads are offered us in strings, to one end of which is usually tied a small image of Osiris, or the winged sun, or the scarabæus with wings. The inexhaustible supply of these beads and images leads many to think that they are manufactured to suit the demand. But it is not so. The blue is of a shade that is not produced now-a-days. And, besides, there is no need to manufacture what exists in the mummy-pits in such abundance.’

A visit to the Boulaq Museum (now the Egyptian Museum in Cairo) shows Warner in rather more thoughtful mood.

‘[T]he almost startling thought presented by this collection is not in the antiquity of some of these objects, but in the long civilization anterior to their production, and which must have been necessary to the growth of the art here exhibited. It could not have been a barbarous people who produced, for instance, these life-like images found at Maydoom, statues of a prince and princess who lived under the ancient king Snéfrou… But it is as much in an ethnographic as an art view that these statues are important. If the Egyptian race at that epoch was of the type offered by these portraits, it resembled in nothing the race which inhabited the north of Egypt not many years after Snéfrou.’

It appears Warner did not subscribe to the contemporary, prejudice theory of an invading race founding the Egyptian Early Dynastic culture – he believed there was a local cultural flowering which then stagnated – though he did admit that there could have been a change of ‘dominating race’ at some point. Writing of this apparent stagnation, he says:

‘I cannot but believe that if it had been free, Egyptian art would have budded and bloomed into a grace of form in harmony with the character of the climate and the people… And to end, by what may seem a sweeping statement, I have had more pleasure from a bit of Greek work… than from anything that Egypt ever produced in art.’

Despite these reservations, Warner’s travels in Egypt and the Levant awoke in him a taste for archaeology, and though the vast majority of the readily available Internet biographies make no mention of his links with the Society, one by Thomas R. Lounsbury tells us:

‘Egypt in particular had for him always a special fascination. Twice he visited it—at the time just mentioned [1875-76] and again in the winter of 1881-82. He rejoiced in every effort made to dispel the obscurity which hung over its early history. No one, outside of the men most immediately concerned, took a deeper interest than he in the work of the Egyptian Exploration Society, of which he was one of the American vice-presidents. To promoting its success he gave no small share of time and attention.’

Warner died in 1900, after collapsing during an afternoon walk. Mark Twain was one of the pall bearers at his funeral.

Further Reading:

Fields, J. T. 1904. Charles Dudley Warner. New York: McClure, Phillips & Co. Available online here.

Lounsbury, T. R. 1896. 'Biographical Sketch', in C. D. Warner, The Relation of Literature to Life. Available online here.